Furthermore, goals help organize behavior over time and across situations and guide attention and behavior.” The very act of committed activity is health promoting.Īs with Selection, we each seek optimization in varied and distinctive ways. To feel committed to goals contributes to feeling that one’s life has a purpose. “Selection promotes successful aging in a number of ways. But I can take long walks and I can write for hours, and they take up the room once occupied by more demanding activities.īaltes’ emphasizes elective selection. No matter how I dream, I’m never going to play basketball again, to take one absurd example. Unless we want to give up, all of us need to accept the loss of some goals. In contrast, loss-based selection is a response to the loss of previously available resources that are necessary to maintain functioning.” For instance, I now walk to get in shape where once I ran. “Elective selection aims at achieving higher levels of functioning. There are two types of selection: elective and loss-based. Once you identify your goals and decide you have a reasonable chance of reaching them, you have to commit to them. The key is to carefully align your desires and your resources to attain your goals.

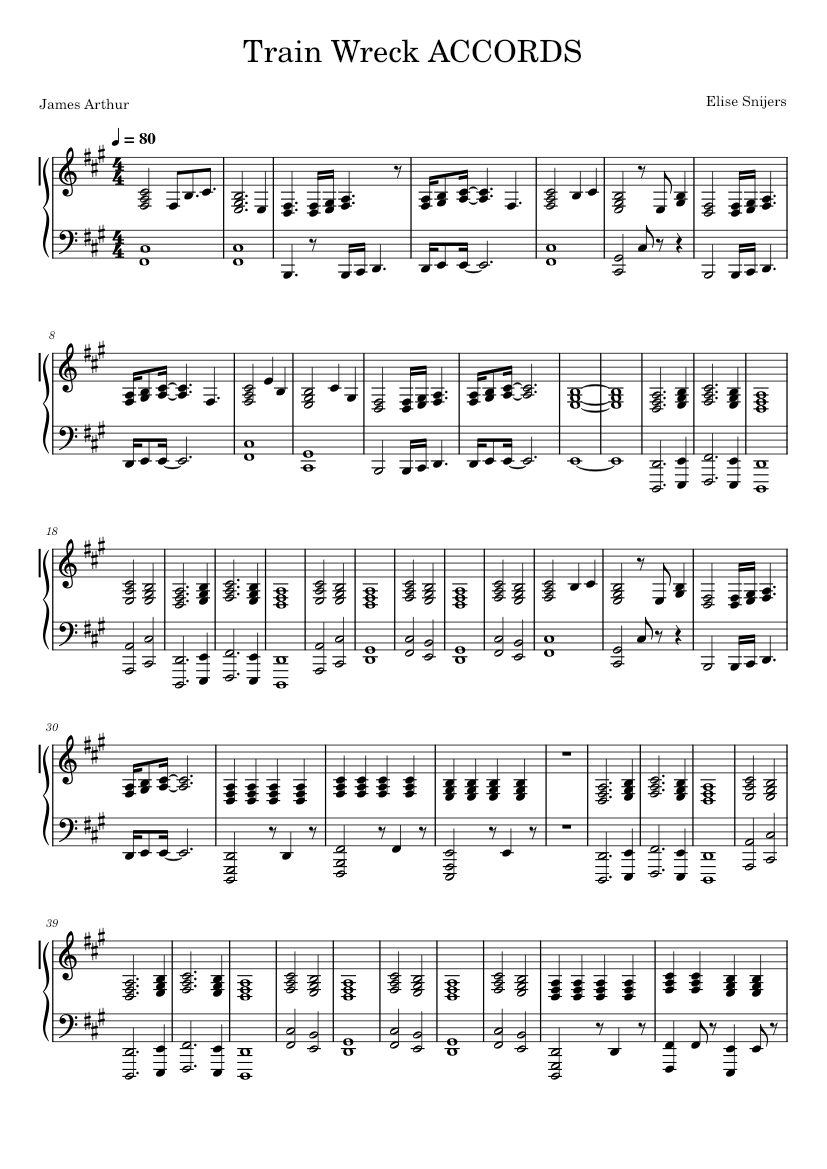

You might want to paint landscapes, to construct a Japanese garden, or to visit exotic, distant places. Selection asks us to develop and commit ourselves to obtainable goals. “…to counteract his loss of mechanical speed he now used a kind of impression management, such as playing more slowly before fast segments to make the latter appear faster.” This is Compensation. The third strategy required a kind of slight of hand. At an old age, he could prepare his chosen repertoire better than in his youth. Rubinstein practiced each of the selected pieces much more than in the past, and much more than he could if he continued to play a larger repertoire. The second part of the strategy is called Optimization. This kind of Selection, Baltes tells us, is the first of a three-part strategy for successful aging. First, said the maestro, he plays fewer pieces, and not just fewer: he limits himself to those he loves and is still able to master.

#Piano prodigy arthur koch tv

One day, when Rubinstein was eighty-one, an awestruck young TV interviewer asked him how he had sustained his virtuosity so far into old age. Even in his dotage, one critic wrote, he could “transmit the joy of music.” At an age when most musical artists slow down, Rubinstein was giving two concerts a week. He was known for his extraordinary vitality. He played to sold-out houses well into his eighties, dazzling audiences with his virtuoso renditions of Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Stravinsky, and others. Just in case you are too young to remember, Rubinstein may have been the greatest concert pianist of the twentieth century.

The eminent psychologist, Paul Baltes, loved to tell a story about the very eminent pianist, Arthur Rubinstein, that points the way. The important question is how best to deal with decline in ways that bring satisfaction. We can’t be blind to the deficits of aging, but we needn’t wallow in them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)